International Journal of Marine Science, 2017, Vol.7, No.33, 316-343

326

the Cuban fishery was active, there was a negative impact on the haplotype pool of the WC rookeries with smaller

Nr, the haplotype EiA43, and other infrequent haplotypes. The negative impact of the Cuba fishery is even more

marked if individuals from the same sources are also subject to consumptive use or affected by other

anthropogenic causes as in the case of Pearl Cays rookery (Campbell et al., 2010). For the orphan haplotype

EiA24, also frequent in the region (Velez-Zuazo et al. (2008): N=2, Blumenthal et al. (2009a): N=11), the

interpretation is that JR is a migratory route of individuals born in WC rookeries although these individuals have

not yet been characterized genetically or there is insufficient sampling. Consequently, by means of a different

approach, the present work corroborates the study of Cazabon-Mannette et al. (2016): the need to prioritize

sampling and conservation efforts of the "genetically unknown" rookeries or others with poor monitoring. In

addition, the MSAgr with both sequence lengths share the increased contributions of the MI and BaL rookeries in

the non-adult aggregation of JR, indicating that the most inclusive criterion will favor the representativeness of

those sources with higher Nr and common haplotypes and thus, the criteria of importance biased towards these

sources. Finally, although Cuba permanently abandoned the legal chelonian fishery, other countries in the region

continue to exploit these resources either legally (

i.e.

Turks and Caicos: Stringell et al. (2013)) or illicitly. Thus, it

is necessary to apply these analyses in conservation and management, but researchers and managers should be

cautious in their interpretation of the results, and they should use other approaches and complementary data.

These results reveal new data that will strengthen the analysis of regional management units, a new approach that

extensively examines published information to coordinate conservation and research strategies (Wallace et al.,

2010; 2011). In addition, researchers could consider and evaluate if the MSAoa is applicable to the other sea

turtles species, which has different migratory behavior, occupies regions that are more extensive and presents

diverse management and conservation conflicts.

3 Materials and Methods

3.1 Study area and individual sampling

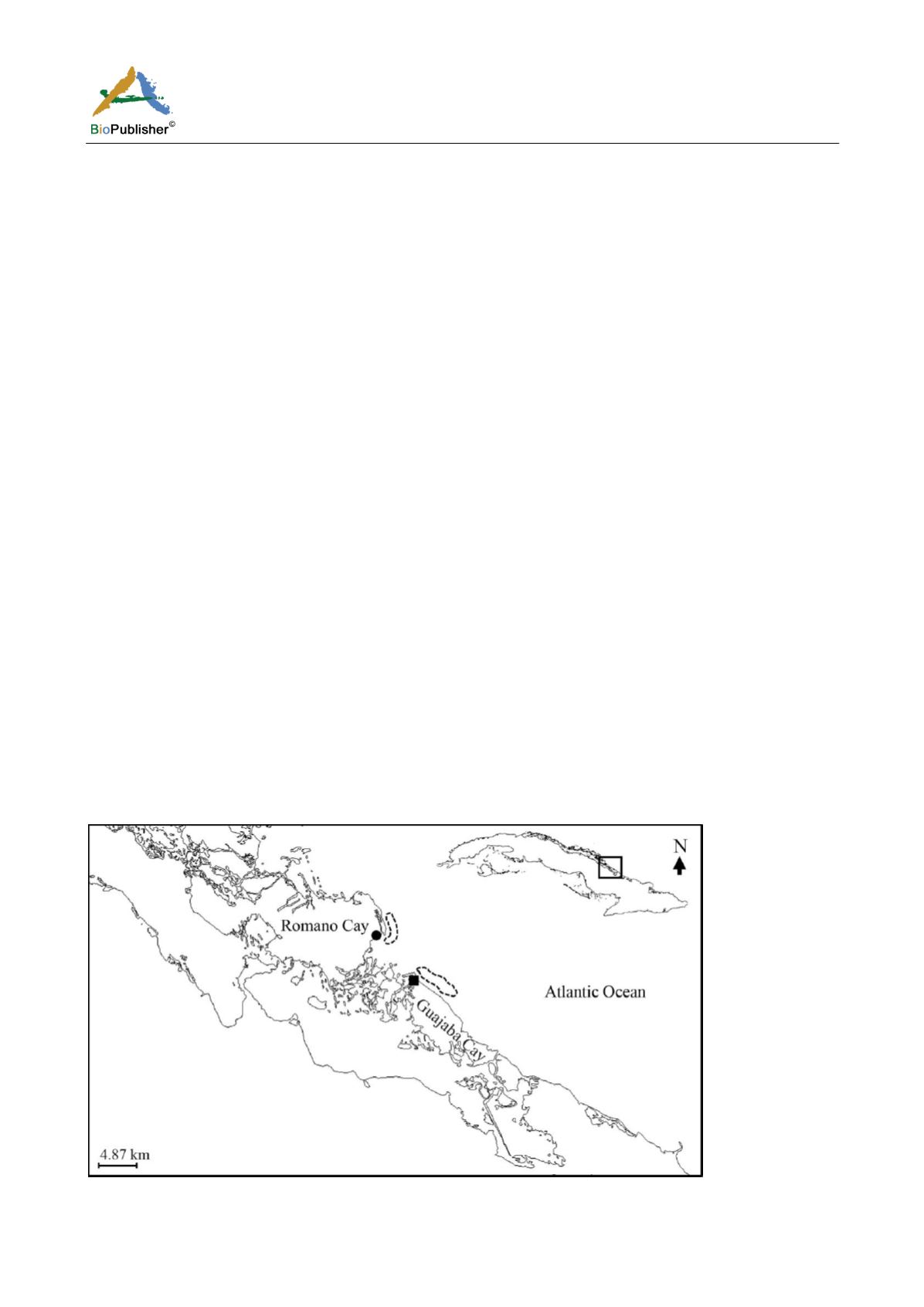

The individuals of

E. imbricata

sampled in this study were those harvested in the legal sea turtle fishery located in

the offshore platform surrounding the fishing settlements "El Mangle"[22

o

00‖12’N; 77

o

26‖48’O] (Romano Key)

and "Montañés"[21

o

56‖06’N; 77

o

34‖12’O] (Guajaba Key), which both belong to fishing zone D (JR) of the

Cuban platform (Figure 4). Harvests were made during the last periods of active legal fishery (January-April and

August-December) during 2004 (N = 95), 2005 (N = 106) and 2006 (N = 48). The place where sea turtle nets were

located constitutes a migratory route of

E. imbricata

and the rest of the area serves as a foraging ground for

Chelonia mydas

and

Caretta caretta

(Lee-González et al., 2015).

Figure 4 Geographical representation of the sea turtle legal fishery in Jardines del Rey (Cuba) from 2004 to 2006

Note: Black circle: El Mangle, black square: ―Montañes‖, black dashed line: fishing aggregation