基本HTML版本

Intl. J. of Mol. Evol. and Biodivers. 2011, Vol. 1, No. 1-5

http://ijmeb.sophiapublisher.com

3

Wald χ

2

=0.049, df=1, P=0.849; air temperature: Wald

χ

2

=0.437, df=1, P=0.509; wind speed: Wald χ

2

=0.582,

df=1, P=0.445).

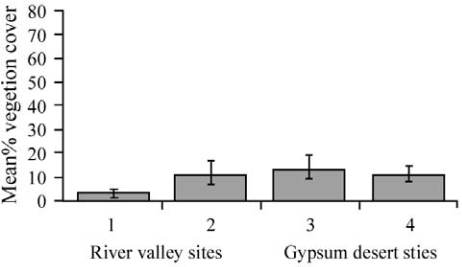

Figure 4 The mean percent of vegetation cover per site

Note: Kruskal-Wallis Test shows cover was not significantly

different per site (χ

2

=2.412, df=3, P=0.491)

2 Discussions

2.1 Escape distance

Since lizard abundance and vegetation cover did not

differ significantly between sites, this indicates that

lizard abundance is not related to vegetation cover.

This is surprising because Stamps (1983) showed that

vegetation structure played a critical role in reptile

habitat selection for predator escape. Additionally, this

vegetation cover has also been used for foraging

(Karasov and Anderson, 1984), and mating (Diaz and

Carrascal, 1991).

Algyroides marchi

is a lizard

endemic to the mountainous region of south-east

Iberian Peninsula. The more stoney and vegetated the

environment, then the less abundant they are (Rubio

and Carrascal, 1994). This could relate to

A.

erythrurus

and

Psammodromus

sp,

which could

explain why lizard abundance was not correlated with

vegetation cover (Figure 3; Figure 4).

The habitats did not differ in percent vegetation cover

(Figure 1). This is supported by previous research;

both

P. algirus

(Diaz and Carrascal, 1991) and

A.

erythrurus

population densities are correlated with

leaf litter and low dense shrub cover (Martín and

López, 2003), which was available in similar amounts

on all of our sites. Hence, this is also why the

Mann-Whitney Test showed that lizard species did not

differ in their relative escape distances.

2.2 Lizard abundance

One would expect morning counts of lizards to be

greater than in the afternoon. In the morning,

A.

erythrurus

were more active in the river valley, while

in the afternoon, were more active in gypsum desert

(Figure 2). Busack (1976) showed that while

A.

erythrurus

activity peaks in the morning, adults stay in

cool microhabitats but within their thermal limits,

which allow them to remain active throughout the day.

A. erythrurus

was the only species found on April 3, a

cloudy day when the air temperature was lower and

the relative humidity was higher, which support

Busack (1976)’s results. In contrast,

P. hispanicus

cannot raise their body temperatures on cloudy days

via basking, and hence are unable to forage for long

periods of time (Patterson and Davies, 1984), which

may explain why they were not seen on April 3.

Additionally,

A. erythrurus

could be found in the river

valley in the morning. However, it should be noted

that there was a high chance of duplicate sightings of

the same individual as we were unable to mark the

species we documented.

Given the desert’s natural sloping landscape, this

could have been a reason why more lizards were

found there (Figure 2). Likewise, the aspect was also

significant, as nearly all of the lizards (n=44) were

sighted where the sun was hitting the ground, and only

(n=3) were not. Bohorquez-Alonso et al (2011)

discovered

Gallotia galloti

, another Lacertid, were

mostly found oriented parallel or perpendicular to the

sun. Also, Arribas (2010) studied activity and

microhabitat selection between two Pyrenean rock

lizards, both Lacertids found in Spain. He discovered

that

Iberolaceria aurelioi

were found on steeper areas

than

I. bonnali

and

I. aranica.

Further studies should

be conducted analyzing slope together with aspect to

determine if the sun is hitting the slopes in the gypsum

desert more directly in the afternoon than the evening,

which would explain our result.

The Fisher’s Exact Test showed that the different

species of lizards had no preference for a particular

habitat. One possible explanation could be because

they have evolved adaptations for both environments.

For example, another lizard found in our study area,

the ocellated lizard (

Lacerta lepida)

is found in warm,