Basic HTML Version

International Journal of Marine Science 2013, Vol.3, No.24, 187-192

http://ijms.sophiapublisher.com

189

So far, no stock assessment for skipjack tuna in the

Indian Ocean and MSY has been estimated. Stock

should be closely monitored. Evidence from

retrospective records strongly suggests that major

structural and functional changes due to overfishing of

tunas occurred in Indian Ocean in recent years. Severe

overfishing derives species ecological extinction

because overfished populations no longer interact

significantly with other species in the community

(Jackson et al., 2001). Periodic reassessment of the

tuna potential is also required with adequate inputs

from exploratory surveys as well as commercial

landings and this may prevent any unsustainable trends

in the development of the tuna fishing industry in the

Indian Ocean.

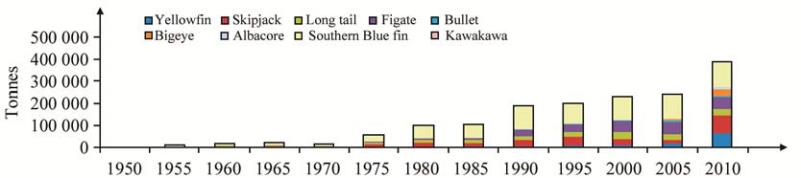

3.3 Tuna production of EEZ of India

Annual marine fish production in India during 2010

was 3.07 (mt) against a catchable potential of 3.93 (mt)

(CMFRI, 2011). The Indian tuna fishery comprises two

distinct segments, the coastal fishery and oceanic

fishery. The oceanic fishery uses exclusively longlines,

targeting large deep-swimming yellowfin and bigeye

tunas. Tuna constitutes one of the important marine

fisheries resources of India having an estimated annual

catchable potential of about 2.78 lakh t in the EEZ.

Coastal resources almost fully exploited and current

focus is on oceanic/deep sea resources. India is yet to

find a place in the tuna map of the Indian Ocean. The

fishery resource of estimated potential tuna and tuna

like species is 2,50,000 t; however, current production

is around 65,863 t, most of which constituted by coastal

tuna species. Figure 3 illustrates all Indian tuna

production which has continued to increase with

fluctuations from 63,633 t during 2001-2005, 78,400 t

during 2006-2010, and 65,863 t in 2010. However,

during the last couple of year’s landings in drift gillnet,

hook and line and troll lines operated by small and

medium sized mechanized vessels are reported to have

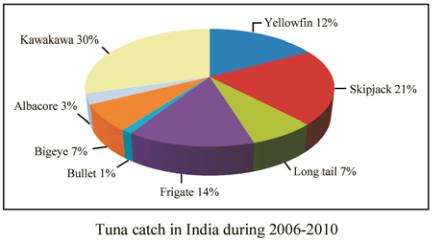

increased marginally (IOTC, 2011). Of the total tuna

landings oceanic species formed 47% and neritic

species 53%. Among the oceanic species skipjack

constituted 21% followed by yellowfin 12%, bigeye

7%, and albacore 3% (Figure 4). Among the neritic

tunas, kawakawa (

Euthynnus affinis

) was dominant

(30%) followed by frigate tuna (14%), longtail tuna

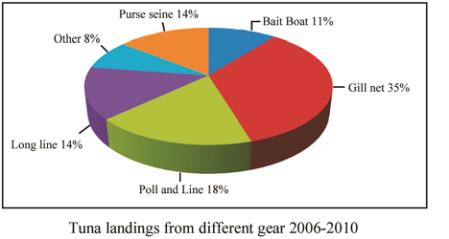

(7%) among others. In the tuna landings from the

Indian coast, gillnets accounted for about 35% of the

catch, pole and line 29%, long line 14 %, purse seine

14%, and the remaining by a variety of other gears 8%

(Figure 5). The present annual export of tuna and tuna

products amounts to 35,000 t valued at $53.22 million

dollar, the major importing countries were Southeast

Figure 3 Trends in tuna catch in Indian EEZ from 1950-2010

Figure 4 Species-wise contribution of tuna catch in Indian EEZ

from 2006-2010

Figure 5 Gear-wise contribution of tuna in Indian EEZ from

2006-2010